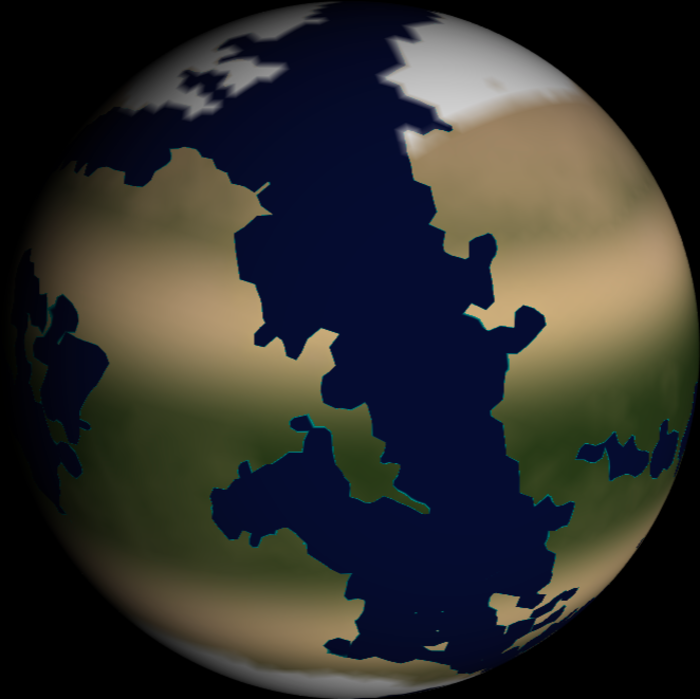

There have been some major changes recently to the appearance of the simulation. I’ve gone through great pains to learn physical rendering techniques in an effort to eventually model how atmospheric compounds affect climate. Those two topics might not sound interrelated, but it turns out they share a lot of the same equations.

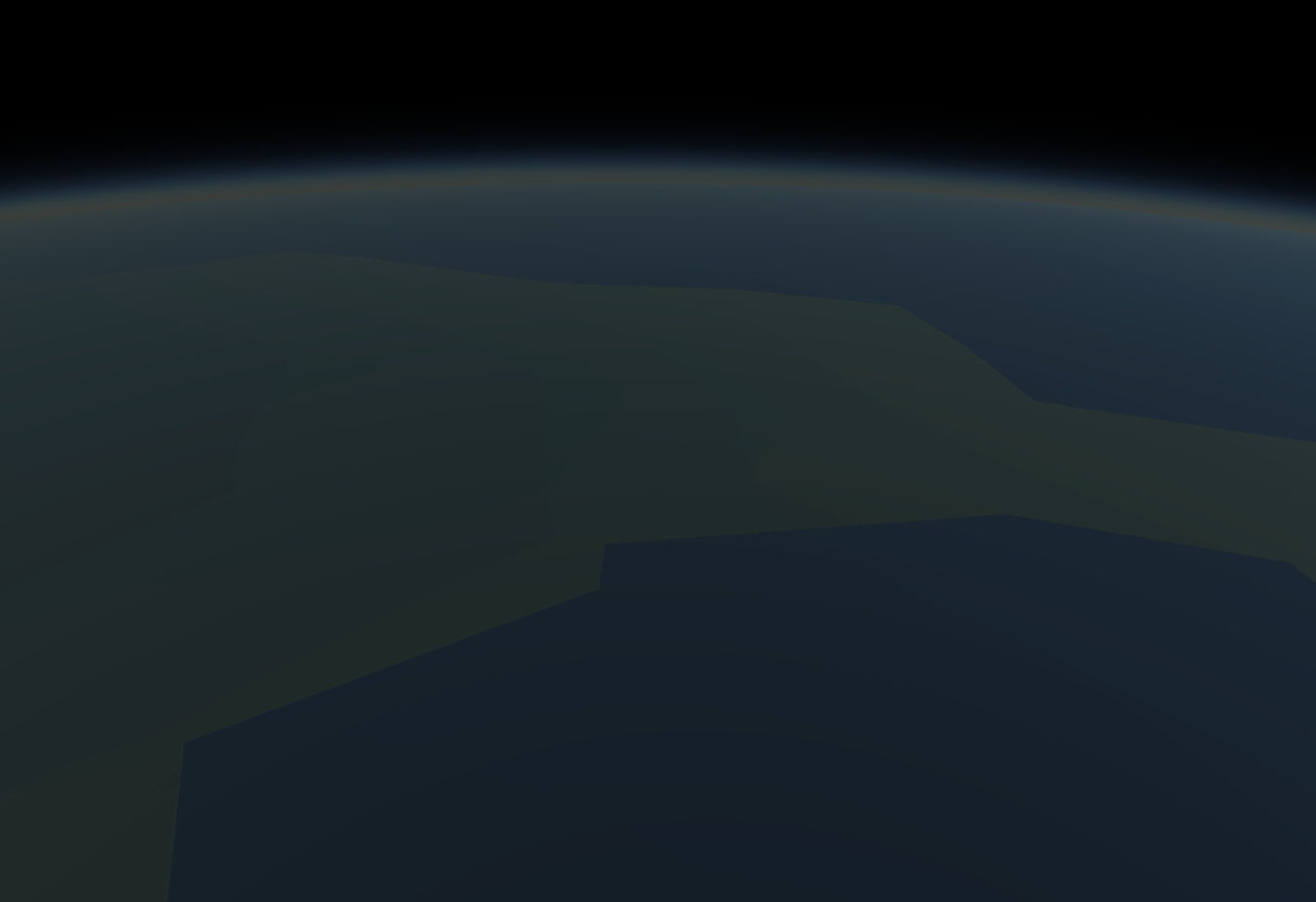

What I want to discuss today is one particular aspect of this new rendering model: atmospheric scattering. Zoom into a planet really close and you’ll see how the atmosphere forms a haze:

How does it do this? Well, it’s a long story, and I won’t describe it in full detail. There are already plenty of resources available online that teach you how it’s done. I highly recommend reading Alan Zucconi’s series on atmospheric scattering, if you’re interested in the topic.

I pretty much use the same technique as Alan Zucconi, but there is one significant improvement I made that I want to talk about. This was an improvement I made to combat performance issues when rendering with multiple light sources. Tectonics.js has a nifty feature where it samples light sources from across several points in time. This is done to create a “timelapse” effect when running at large timesteps.

I didn’t want to toss out this feature in order to implement atmospheric scattering, but I have to admit: it’s a pretty usual requirement for an atmospheric renderer. Most of the time, atmospheric renderers assume there is only one light source, that being the sun. You could trivially modify an atmospheric renderer to run on multiple light sources, but let’s consider the performance implications of doing so.

Atmospheric renderers use raymarching to find something known as the column density along a path from the viewer to the light source. You might see this mentioned here as the “column density ratio.” When we say this, we mean the column density expressed relative to the density of air on the surface of the planet. Most standard atmospheric renderers are implemented as follows:

for each point "A" along the view ray "V":

for each point "B" from A to light source "L":

sum up the column density ratio

You will notice the implementation above uses two nested for loops. What if we added support for multiple light sources? We would need to add another for loop:

for each point "A" along the view ray "V":

for each light source "L":

for each point "B" from A to light source "L":

sum up the column density ratio

We now have three nested for loops, each of which might run about 10 iterations in our use case. We’re looking at something on the order of 1000 calculations. That’s 1000 calculations for every pixel, for every frame. This is madness.

So is there anyway we can pare this down? Can we eliminate one of the for loops?

Well, fortunately for us, this code is not very well optimized. We need to consider what we’re doing here: we’re summing up the mass that’s encountered along a series of infinitesimally small steps from “A” to “L”. In essence, we’re calculating an integral.

To be more precise: we’re trying to find the integral of density from points “A” to “L”.

The integral looks like this:

`int_A^L rho(x) dx`

Here the density `rho` is defined by the Barometric formula

`rho(x) = exp(-(h(x))/H)`

where `H` is the scale height of the planet, and height `h` is defined by the distance formula minus the planet's radius `R`

`h(x) = sqrt(x^2 + z^2) - R`

Here, `x` represents some distance along the ray relative to the closest approach, and `z` represents the distance to the center of the planet when at that closest approach (see diagram on the left)

So all together, we’re trying to solve:

`int_A^L exp(-(sqrt(x^2 + z^2) - R)/H) dx`

Solve this integral, and you will be able to completely eliminate a nested for loop from your raymarching algorithm. That’s a factor of 10 performance improvement!

If this were a college calculus course, you might think to use integration by substitution. This results in the following expression:

`-H/(h'(x)) exp(-(h(x))/H)`

However this produces bogus results when the ray just barely grazes the planet, such that `z approx R` and `x approx 0`. This is because the height changes very little in these circumstances, so `h'(x) = 0`. In essence, we divide by 0, and results near this singularity will look unrealistic.

Fortunately, we only need something that looks convincing, so we can afford to make approximations. All we need is a good approximation for height whose derivative never reaches 0. I've tried several approaches, but the best I've found so far uses a quadratic approximation for height. It's derivative still eventually reaches 0, but you can stretch out the approximation by some factor `a` to ensure it never gets anywhere near 0 for any positive value of x.

`h(x) approx 1/2 a h''(x_b) + h'(x_b) + h(x_b)`

Here, `x_b` is a sample point along the path through the atmosphere. If `x_0` is the point at which we encounter the surface, and `x_1` is the point at which we encounter some arbitrary "top" of the atmosphere, then `x_b` can be thought of as a point between them, defined by a fraction b:

`x_b = x_0 + b(x_1-x_0)`

For my implementation, I define the "top" of the atmosphere to be 6 scale heights from the surface. Under these circumstances, I set `b = 0.45` and `a = 0.45`. I find this gives pretty good approximations for column density ratio given virtually any realistic value of `z` or `H`. See for yourself: follow the link here and adjust the sliders for `H` and `z` and see how close the appoximation (red) gets to the actual column density (black)

Lastly, if you’re interested in borrowing some of my code, check out raymarching.glsl.c in the Tectonics.js source code, or just copy/paste the code below:

float approx_air_column_density_ratio_along_2d_ray_for_curved_world(

float x_start, // distance along path from closest approach at which we start the raymarch

float x_stop, // distance along path from closest approach at which we stop the raymarch

float z2, // distance at closest approach, squared

float r, // radius of the planet

float H // scale height of the planet's atmosphere

){

float a = 0.45;

float b = 0.45;

float x0 = sqrt(max(r *r -z2, 0.));

// if ray is obstructed

if (x_start < x0 && -x0 < x_stop && z2 < r*r)

{

// return ludicrously big number to represent obstruction

return 1e20;

}

float r1 = r + 6.*H;

float x1 = sqrt(max(r1*r1-z2, 0.));

float xb = x0+(x1-x0)*b;

float rb2 = xb*xb + z2;

float rb = sqrt(rb2);

float d2hdx2 = z2 / sqrt(rb2*rb2*rb2);

float dhdx = xb / rb;

float hb = rb - r;

float dx0 = x0 -xb;

float dx_stop = abs(x_stop )-xb;

float dx_start= abs(x_start)-xb;

float h0 = (0.5 * a * d2hdx2 * dx0 + dhdx) * dx0 + hb;

float h_stop = (0.5 * a * d2hdx2 * dx_stop + dhdx) * dx_stop + hb;

float h_start = (0.5 * a * d2hdx2 * dx_start + dhdx) * dx_start + hb;

float rho0 = exp(-h0/H);

float sigma =

sign(x_stop ) * max(H/dhdx * (rho0 - exp(-h_stop /H)), 0.)

- sign(x_start) * max(H/dhdx * (rho0 - exp(-h_start/H)), 0.);

// NOTE: we clamp the result to prevent the generation of inifinities and nans,

// which can cause graphical artifacts.

return min(abs(sigma),1e20);

}

// "approx_air_column_density_ratio_along_3d_ray_for_curved_world" is just a convenience wrapper

// for the above function that works with 3d vectors.

float approx_air_column_density_ratio_along_3d_ray_for_curved_world (

vec3 P, // position of viewer

vec3 V, // direction of viewer (unit vector)

float x, // distance from the viewer at which we stop the "raymarch"

float r, // radius of the planet

float H // scale height of the planet's atmosphere

){

float xz = dot(-P,V); // distance ("radius") from the ray to the center of the world at closest approach, squared

float z2 = dot( P,P) - xz * xz; // distance from the origin at which closest approach occurs

return approx_air_column_density_ratio_along_2d_ray_for_curved_world( 0.-xz, x-xz, z2, r, H );

}